Artists have been using technology for centuries to further their craft. Be it the camera obscura or Adobe Photoshop, we have always found ways to improve what we do. I find that one of the biggest differences in my painting experience between painting from life and from a photo is getting lost in the small details. Its easy to do in a high-resolution photograph blown up on a 24" screen and when you don't have a model's comfort to consider its easy to forget the time and loose yourself in the process of overworking every little area. Yet, when painting from life it seems so much easier to see the subject as whole, block in the proper shapes and colors, and work towards detail as time allows. So, how do we solve this problem? Obviously, paint from life! Except for when that isn't a realistic option, most of the time for me. So I'll take the next best thing: Photoshop.

Here's our beginning photo reference. Its fine as it is, good value scale, obvious light and shadow. But there are also tons of little details one could get overly focused on. How do we fix that?

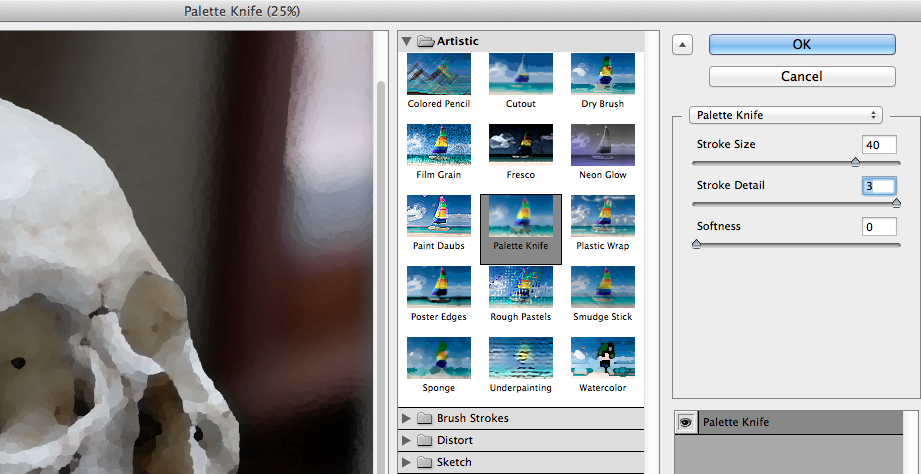

The first thing I recommend after opening your image in photoshop is copying your image into a duplicate layer. Then open the Filters Gallery and select the 'Palette Knife' filter. Adjust your sliders as you wish, the larger the stroke size the blockier the reference photo becomes.

Once you've completed your adjustments you'll end up with a photo like this:

A much more simplified version of the original. The value and temperature changes are more obvious with the details subdued. To me this feels as close to painting from life as I can get without having a model in front of me.

As I progress through the painting and start layering I'll adjust the opacity of the knifed layer, slowly introducing the details back into the reference.

Eventually I'll turn the knifed layer all the way off and allow myself to get lost in the details now that the structure of my painting is properly built.

Some may consider this cheating but I doubt they'd drill a hole with hand drill when they have a Black & Decker sitting on their workbench.